A good set of ancient-style exercises is essential to the ancient learning experience. Ancient pupils did not listen passively; they learned by doing. We advise starting with a reading exercise, both because reading exercises were absolutely central to ancient schooling and because ancient reading is so different from modern reading that it makes an excellent introduction to the ancient educational world.

After reading it is a good idea to have a suite of other exercises that different children do in different orders, because that saves on materials: if you have thirty children needing wax tablets at once you need thirty tablets, but if only a third of them need tablets at any one time you need only ten tablets. Good candidates for these other exercises are copying, dictation, memorisation, arithmetic and Latin – but these all take time to experience properly (minimum 20 minutes each for most exercises, often 30 each for Latin and dictation), and pupils tend to get upset if there was something they saw others doing and did not get to try themselves, so it is best not to try to put too many exercises in unless you have a lot of time.

Ancient-style exercises are hard, and most pupils will not be able to do them perfectly. Some cannot do them at all well – but that is fine, since struggling unsuccessfully with exercises was part of the authentic ancient experience. After all the goal of a re-created ancient school is not to master the particular exercises provided, but to find out what school was like for ancient pupils. But because many modern pupils are used to easier tasks with higher standards, they may get discouraged and stop trying – which is not fine, because then they don’t get the ancient experience. So it is worth telling them at the start (and repeating later) that they shouldn’t worry if they can’t do the exercises very well: as long as they honestly try to do the best they can on the exercises, they will do perfectly on the real goal, which is finding out what ancient learning was like.

The independent work involved in ancient learning can be a challenge for some modern pupils. It is nevertheless worth persuading them to try it, rather than helping them through the exercises. Because getting through the exercises isn’t the goal: if pupils ends up with a perfect grasp of a text but only because of having been talked through it by you, they won’t have learned anything about ancient education.

Reading

For reading pupils should be given an ancient-style text and asked to spend ten to fifteen minutes deciphering it and practising reading it aloud, before coming back to a teacher to read it aloud and answer questions on it. For this they need a suitable text written in a suitable fashion. Ancient Latin speakers typically learned to read on the Aeneid and ancient Greek speakers on the Iliad, even though both those poems are composed in elevated, poetic language that became more outdated and therefore more challenging with each passing century. We find that for most English-speaking pupils the best approximation to the ancient experience is an extract from Dryden’s translation of the Aeneid or Iliad. Dryden’s English is elevated, poetic, archaic, and extremely beautiful; his verses are so obviously poetic that their rhyme and metre help pupils understand how to pronounce the words, the way the original dactylic hexameter helped ancient pupils. In our experience, pupils aged ten and up can usually do well enough on Dryden’s language to make it worth giving to them, but younger ones often cannot and need something easier; we give them fables of Phaedrus in a modern translation.

Exactly how the reading passage should be presented depends on what kind of ancient school you are re-creating. For Greek-speaking schools there should be no word division, punctuation, or lower-case letters, just a string of unadorned capitals. For Latin-speaking schools from the imperial period the same is true, but for a Republican-era Latin school one divides words using interpuncts, that is raised dots between words – not spaces, which were introduced as word dividers in the ninth century AD. Young children (under ten) often need interpuncts; that is a reason to do an early Roman school if your pupils are young.

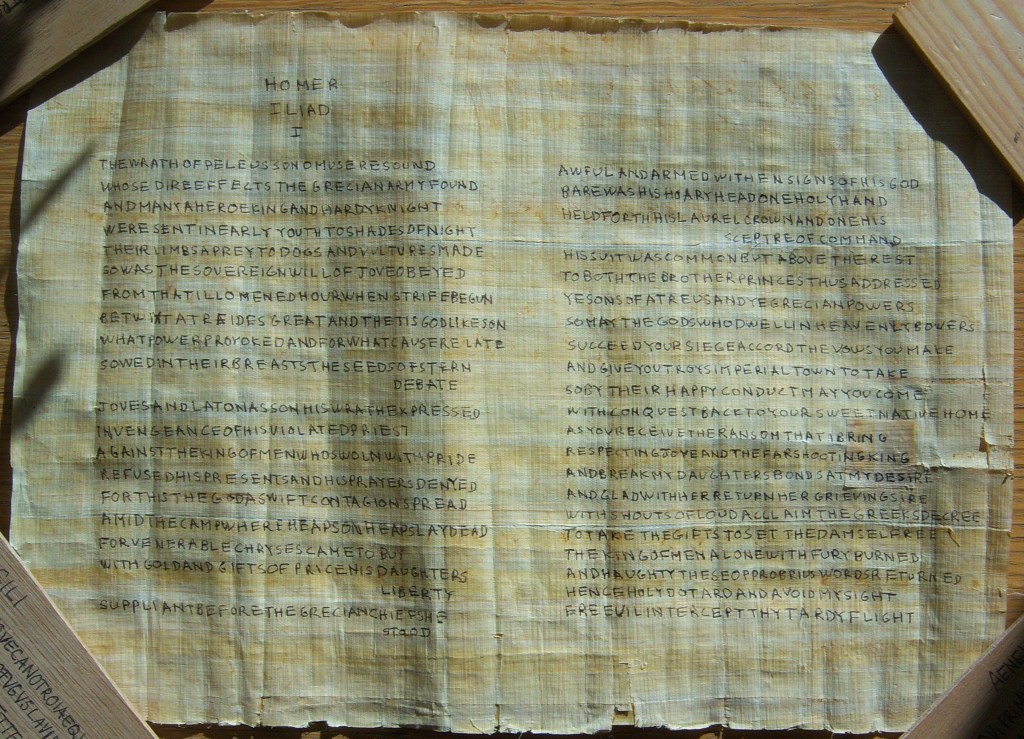

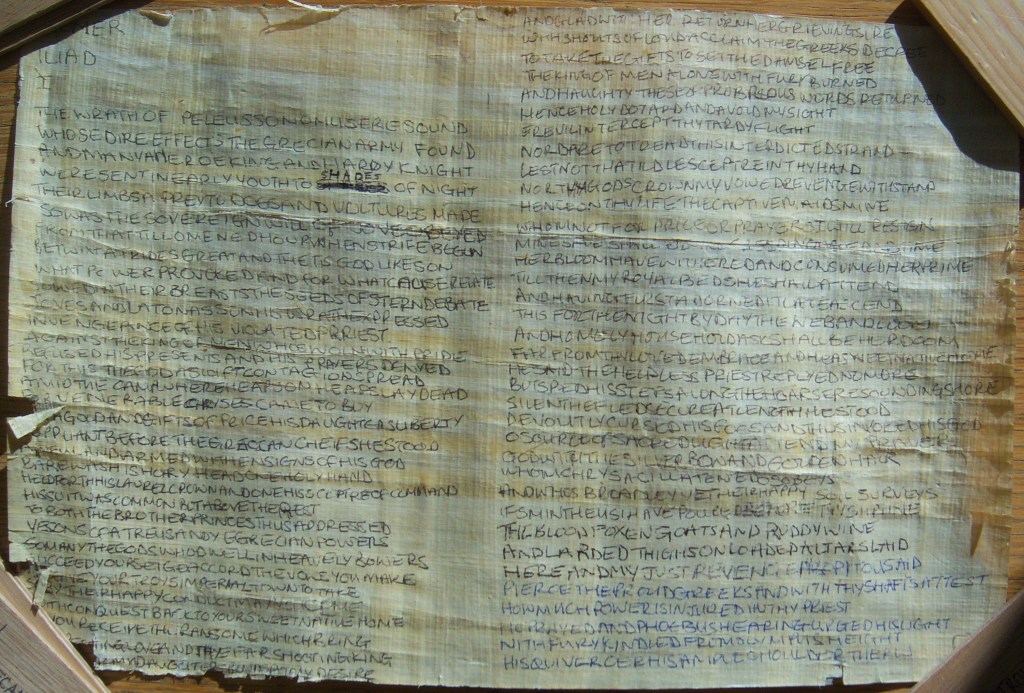

Ideally the reading passage should be hand-written on papyrus or wooden tablets (see here for which to use when). This takes a lot of time, particularly as the fact that reading should be the first exercise and is therefore done by all pupils at the same time means that one needs enough copies for everyone (including teachers) to have one at the same time. But it is worth that investment, because a printout is just not convincing. When copying out the passage one should leave generous margins, not only because the ancients did but because that causes the text to remain legible for longer, the margins being where wear and tear strikes first. One should also write clearly and legibly, with space vertically between the lines and also horizontally between the individual letters: if the letters touch each other even slightly the whole text becomes much harder to decipher. Here are three papyri, each about ten years old:

Try not to make copying mistakes, but if you do make one, just cross it out, write in the correct words, and go on: crossed-out errors were a common feature of ancient books. (Uncorrected errors were also common, but we don’t recommend introducing those, because they tend to make ancient-style reading simply too hard for people who aren’t used to it.) To avoid multiplication of errors it is safer to copy each papyrus from the same original, rather than copying from the copies already made.

Be sure to make your reading exercise long enough and hard enough that no pupil will be ready to recite in under ten minutes. It takes at least ten minutes for a whole class to enter the schoolroom, and if the ones who entered first start taking teacher time to recite before the ones at the back of the queue have come in, those have to stay outside longer than is fair to them.

When giving pupils the reading exercise it is useful to explain what it is and why it is the way it is. We also advise telling pupils that they should spend ten to fifteen minutes working on it and then come to recite whatever they have managed to prepare in that period; there is no set amount of text they need to get through. When they come up to recite, they should get the authentic ancient recitation experience. This should involve about 5 minutes of a teacher’s undivided attention (if no teachers are free the pupils need to queue for recitations). A pupil reciting should stand facing the teacher, who therefore needs to take another copy of the text to look at. First the pupil reads aloud; as long as this is going well the teacher shouldn’t interrupt. When the pupil reaches the end of the well-prepared section (as evidenced by stopping or by a sharp decline in the quality of the recitation), forget about the rest of the text and focus only on what’s actually been read. Ask the pupil to summarise it in their own words and then ask about the meaning of any words or phrases that you heard them stumbling over or that you expect them to have trouble with. Talk them through the passage until they genuinely understand both what it means and what the words are that give that meaning; try as far as possible to achieve that understanding by asking questions and getting the pupil to think, rather than by just giving out information. Ask the pupil if there are any remaining words or ideas that they don’t understand or want to ask about, and do your best to answer their questions (of course admitting honestly when you don’t know the answer). Only ask questions about the text itself, not about its wider context; for example when the passage is the beginning of the Iliad you can ask who Peleus’ son was, who Atreus’ son was, and who Jove was, but not what the causes of the Trojan War were or where Achilles’ weak spot was. You can also ask what individual words mean, where to put which punctuation, etc.

If the recitation does not go well even at the start, you need to assess the situation. How long has that pupil spent preparing to recite? Those who come up after less than ten minutes haven’t done the preparation properly and need to be gently but firmly sent to sit out of reach of other pupils and do it properly: independent study is an essential part of ancient education. (By this I don’t mean that pupils shouldn’t work together to prepare the reading; genuine collaboration is authentic and absolutely fine. But the ones who come up early normally will not work together if sent back to the company of others; they will just distract the others.)

Pupils who have genuinely tried but not got very far should recite a few lines with your help. This means you need to be able to read the text aloud, fluently and metrically. You can read to them a line or two (whichever makes a good sense unit), ask them to repeat it aloud after you until they can do so convincingly, ask them which words in it they know or do not know, ask what it means, etc. Again you want to spend about five minutes (if you spend longer the queues of other pupils get too long) and have them end up understanding a passage, but under these circumstances the passage may be only two or three lines. That is actually enough to get the hang of ancient-style reading.

Copying

Ancient pupils learned to write by hand-copying texts, often ones that they could not understand. We find that modern pupils dislike copying things they do not understand, plus it is very challenging for teachers to read what pupils have written (especially on wax tablets). It works better to have pupils copy a text that they can understand, and ask them not only to copy it but then to practise reading it aloud and finish by reciting to a teacher in the same way as for the reading exercise. That way the teacher never has to read the pupil’s writing. Copying can be done on wax tablets, with pen and ink on ostraca, or both.

In principle pupils can be given a wooden tablet containing the text to be copied, but in practice there isn’t anywhere for the pupils to put that tablet while copying, since they don’t have desks. It is easier (and authentic) to copy from the walls. So we paint suitable texts in red paint on large strips of fabric and drape them on the walls. Only a small number of pupils can sit in front of each text at once, so it’s useful to provide three or four texts and spread them out (and if using ink to put ink-proof floor protection where pupils will naturally sit to see these texts). Let pupils choose which text to copy – but make sure the texts all have lines about the same length, as otherwise everyone will want the text with the shortest lines and may fight over the space in front of that one. It’s also useful to make sure the teachers’ chairs are arranged so that the teachers can see the texts on the walls – but pupils standing in front of the teachers could still obscure the view, so it’s kind to also make the teachers papyrus cheat sheets containing the wall texts. Papyrus cheat sheets also help if you are taking authenticity to the point that the teachers are not wearing glasses, meaning that the short-sighted ones among them cannot actually read the texts on the walls.

Texts for copying should be written like those for reading: all in capitals, no spaces, no punctuation, interpuncts only if in Republican Rome. But if you have used the Iliad/Aeneid for reading, it’s best to provide different texts for copying. Translated fables (Babrius’ version for Greek schools, Phaedrus’ version for Latin ones) work well, but there are also other options, including English poetry (after all ancient students copied poetry originally composed in their own languages, and poems originally composed in English usually make better English poetry than translations). What is vital is that the texts used for copying have the following features:

- They are short enough to fit on whatever the pupils will copy them onto. Pupils can of course copy just the beginning of a text, but then they tend not to understand the content, particularly with fables, whose punch line often comes at the end.

- They are composed in somewhat archaic language, not the ordinary conversational idiom.

- They are still comprehensible (not necessarily immediately comprehensible, but after some thought) when written out ancient style. When choosing texts you can try writing them out this way and give them to a friend or colleague to see if he or she can decipher them, before making a final decision on which texts to use.

- If not actually ancient, the texts should have the type of content typically found in ancient school texts, that is a moral or some other improving lesson, ideally one with which many ancients would have agreed (e.g. ‘don’t be greedy’ is fine, ‘love thy neighbour as thyself’ is not). And of course the texts should have no reference to the modern world or to Christianity. Romantic love is also not a big theme in ancient school texts.

When students come to recite the texts they have copied, the teacher should first make sure that they have brought all the materials back, and then hear the recitation and ask questions as for the reading exercise. If the text is a fable, it’s a good idea to ask what its moral is and make sure pupils grasp that moral.

Dictation

Taking dictation was an important skill in a world where many people could not write, so ancient schoolchildren practised it, in pairs: first one spoke and the other wrote, and then they swapped roles. We find that this works well, provided that the pair comes to a teacher and recites before the swap. We do dictation on wax tablets, because the pairs of pupils need to sit spaced out so that they can hear properly, and that is not compatible with the need for pupils using ink to all sit together on the protected portion of the floor.

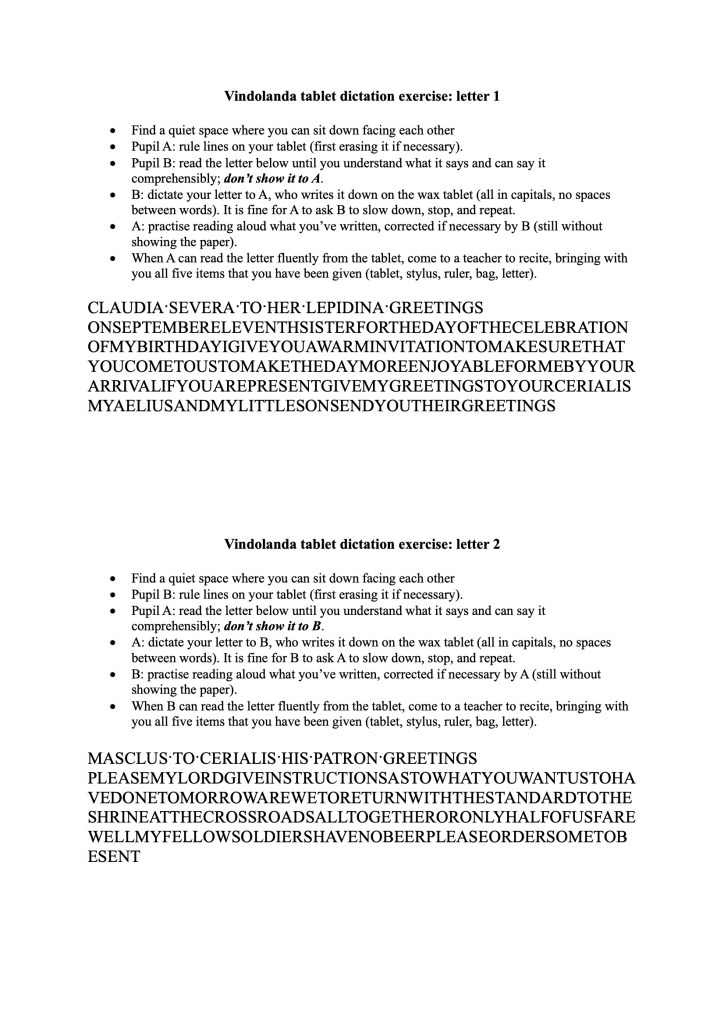

Texts for dictation should be very short (about two sentences long), because dictation is hard and wax tablets are small. For re-enactments of Roman Britain Vindolanda letters are good, because those were actually dictated. For Greek-speaking schools philosophical maxims are useful. We give out the texts for dictation on paper, written ancient style and accompanied by detailed instructions written modern style; written instructions are as inauthentic as the printed sheet of paper, but we find that without them, pupils often do not end up doing any actual dictation: they just copy from the written page.

After writing the dictated text, the pupil should practise reading it aloud and then come to recite and answer questions in the same manner as for reading and copying. At the end of the first recitation the teacher gives out a new text for dictation and asks the pupils to swap roles. It is a good idea to always use the same two dictation texts in the same order, to avoid teachers getting confused about whether a particular pair of pupils are on their first or second dictation.

Memorisation

Memorisation played a central role in ancient education, but it is unpopular among modern children. We therefore tend to keep it in reserve as an extra exercise for pupils who go faster than the others and thus finish all the exercises before the end of the session. (Another option for such pupils is not to have a fixed end time but let each pupil leave when he/she has finished all the exercises. That is beautifully authentic but only works if you have someplace else for them to go, with an activity that works when participants arrive one at a time.) One needs to give such pupils an exercise that can hold them for a while, and that doesn’t have any fun toys attached – if the others see the fastest pupils with new equipment, they too will speed up to get to the last exercise, causing long queues for the teachers. So memorisation is perfect.

If you have three or four fables or short poems on the wall for copying, they can also provide the texts for memorisation: ask the pupils to pick one that they haven’t used for copying, memorise it, think about its meaning or moral, and come to recite and discuss it. If you do not have texts on the walls, you should have some on tablets or papyrus to give out for memorisation.

Arithmetic

Roman arithmetic is very popular with pupils and is good for developing numeracy skills. But it cannot really be explained in writing, so we encourage you to consult our video ‘Introduction to the Roman abacus and counting board’ at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c-2I09cmth0 and the other videos on our You Tube channel: https://www.youtube.com/@ReadingAncientSchoolroom.

Unlike other ancient school exercises, arithmetic needs to be taught in groups. We usually have one arithmetic teacher (two for groups over 30), who first enters the schoolroom when pupils start to recite their reading exercises and to whom the first four to six pupils who finish reciting are sent. Those pupils work together on arithmetic for 20-30 minutes and are then sent off to the literature teachers for writing exercises, at which point the literature teachers send to arithmetic the next four to six pupils who finish other exercises. Try not to send pupils to arithmetic when a group there is halfway through; that puts the arithmetic teacher in a very difficult position.

The fact that arithmetic is a group exercise means that it suffers much less than the other exercises from being taught in a modern setting in the course of a normal school class period.

Latin

Latin is trickier than other exercises, both because it can only be taught by people who actually know some Latin beforehand and because the level of the exercise needs to match the level of the pupils’ Latin knowledge. (There is also an authenticity problem: in a Latin-speaking school you shouldn’t really be teaching Latin as a foreign language, and in a Greek-speaking school you shouldn’t really be teaching Latin at all, because although Greek speakers learned Latin, they did not do it in school. We sometimes get around this by re-enacting the first schools in a newly-conquered province, where the main subject being taught would have been Latin but the pupils wouldn’t have known Latin yet.) You can find actual ancient Latin exercises in E. Dickey’s Learning Latin the Ancient Way and use them as described below; we recommend always putting pupils in pairs for Latin, both because they get better results that way and because pairing allows you to spend ten minutes rather than five going over the students’ work.

- Beginners (this group can include pupils with up to two years of Latin as well as those who do not study Latin at all): pair pupils up and give each pair one of the short dialogues from the Colloquia, presented in the columnar format with the Latin on the left and the English on the right and written ancient-style except that the Latin (but not the English) has interpuncts. Ask the pair to use the English to work out what the dialogue is about and who speaks which lines, and then to practise performing the Latin as a play, with each of them taking one part (or, for dialogues with more than two parts, someone will have more than one part). Then they should think about the Latin words, and then come to recite. When they come to you, ask the pair to perform the Latin; you will be able to tell how much they have understood from how they handle the speaker changes. Interrupt them if they get those wrong; otherwise let them finish and then ask them to summarise the dialogue and explain any tricky points. Ask some Latin questions appropriate to the pupils’ level: for those with no prior knowledge of Latin you can ask what various English words that appear in the right-hand column are in Latin (with persistence you can also get them to work out something about how Latin endings work), and for those with some Latin you can ask what forms various words are in and why they are in those forms.

- Intermediate (that is, pupils advanced or ambitious enough to be insulted by being given a translation): take the Latin part of a short Colloquium dialogue (or a passage from Virgil, or one of the other texts in Learning Latin the Ancient Way) and re-arrange it into a paragraph, written ancient style but with interpuncts. (Only very advanced Latin students can cope without some kind of word division.) Add a 2-column vocab list glossing all the words your pupils will not know, in the order of those words’ occurrence in the text. Glosses should be of the ancient type, that is the Latin should be in exactly the form in which it appears in the text, not in its dictionary entry form, and the translation should reflect the form as well as the meaning. Give this to a pair of students and ask them to decipher, perform and discuss the dialogue as for the beginners’ texts. If these pupils recite well, with correct speaker changes and expression, you don’t need to ask them to translate the Latin – but if they appear not to understand the Latin, ask them to translate it (as a dialogue, each taking a different part).

- Advanced (that is, pupils advanced or ambitious enough to be insulted by the intermediate exercises – but those are very scarce indeed): use a Colloquium dialogue with the original Greek and no English.