The ancient schoolroom space aims to create a different world, in which everything seems to be Roman. Participants feel as if they have been transported elsewhere, and this feeling enables them to act differently from normal.

The schoolroom’s windows were hand painted on translucent cotton fabric by artist Rosemary Aston. In the Greco-Roman Egypt version of the schoolroom, the windows show life along the Nile and are based on ancient wall paintings and mosaics of Nilotic scenes. Having such a beautiful view is probably not authentic – archaeologists think Egyptian schools usually had few or no windows, to keep out the searing sunlight – but we couldn’t resist.

In the British version, the windows (or rather the arches of the porch in which the school is imagined to be held) show a Romano-British town in the later first century AD, with the ruins of a recently-conquered hillfort in the background. These scenes are based on Roman artworks and on archaeologists’ reconstructions of Romano-British architecture.

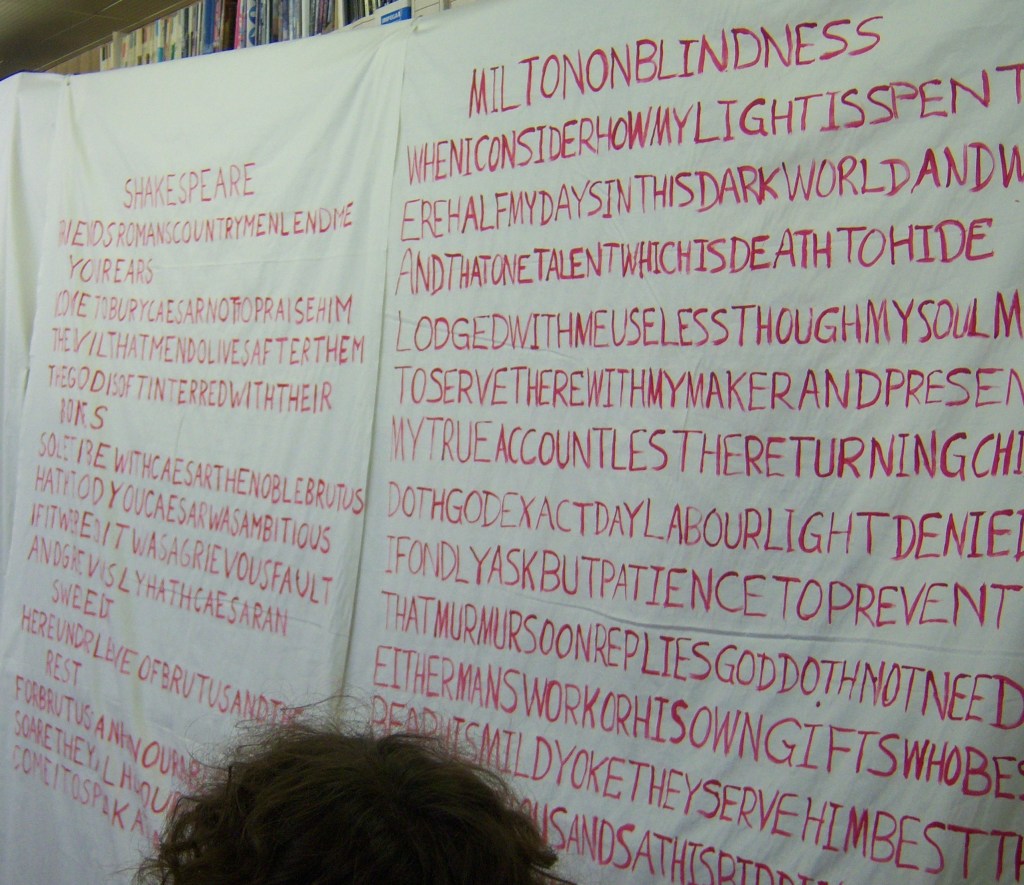

The other walls of the room are of white cotton, which is intended to represent whitewashed masonry (or wattle and daub in the British version — a viewer would not have been able to tell what was underneath the whitewash). In the Egyptian version they are painted with English poems, which participants use for various activities.

This décor is taken from the only Roman school yet securely identified by archaeologists, found in Trimithis, Egypt, and dating to the fourth century AD. It now looks like this, after about 16 centuries of wear and tear:

You can read more about the Trimithis school and the poems on its walls in

- R. Cribiore and P. Davoli, ‘New Literary Texts from Amheida, Ancient Trimithis (Dakhla Oasis, Egypt)’, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 187 (2013): 1–14

- R. Cribiore, P. Davoli, and D. M. Ratzan, ‘A teacher’s dipinto from Trimithis (Dakhleh Oasis)’, Journal of Roman Archaeology 21 (2008): 170–91

- For photographs of the Trimithis schoolroom see also figures 120 to 123 of this article

The reason the poems on our walls are English is that the poems on the Trimithis walls are Greek: Roman citizens in fourth-century Egypt were normally educated in Greek (which was usually their native language) and learned Latin (if at all) as a foreign language. We try to replicate that dynamic by substituting English for Greek, teaching children literature in their native language and Latin as a foreign language. Our poems are by Shakespeare, Tennyson, Housman, and Carlyle (sometimes also Keats and Milton); these reflect the spirit of ancient education better than a translation of a Latin or Greek poem would, by being immediately accessible as great poetry in a somewhat old-fashioned version of the participants’ native language (but not so old-fashioned as to be indecipherable when written without word division). Most of the poems have improving morals, since that was a feature of ancient education, but in a spirit of modern non-judgementalism the morals of the different poems sometimes conflict.

The walls and windows are hung on a frame made of aluminium poles (it was designed as a fruit cage). The poles are each 6 feet long, and their normal configuration creates an interior space of 12 feet by 24 feet, which holds about 30 people. We can also use more poles to create an interior space of 24 feet by 24 feet.

An ancient schoolroom is not a classroom: rather than a space for a large, homogenous group all doing the same thing, it is a space for diverse individuals and small groups doing different things. Typically some participants will be working independently, some will be discussing their work with the literature teachers, and some will be working in a small group with the maths teacher(s).

The literature teachers sit in carved wooden chairs; we use these because they happen to resemble Roman chairs, but they are actually Damascus chairs inherited by the Director from a thoughtful relative.

Pupils sit either on the floor or on a bench running around the edge of the room; we rarely use benches because they lead to arguments about who gets to sit on them — though such arguments are totally authentic.

Neither teachers nor pupils have desks, because the ancients did not use them. For reading, the ancients simply held books in their hands (as in this first-century AD depiction from the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii), since papyrus rolls are not heavy and do not need to be rested on anything.

For writing on wax tablets, which are stiff and lightweight, the ancients likewise held everything in their hands; when writing on papyrus (and presumably on heavy ostraca) they used their laps, specifically the right thigh. We encourage participants to replicate these practices, but they often end up resting materials on the floor, which we let them do even though it is not authentic.

Maths, however, requires a table. In antiquity people would probably have stood around the table, as in this relief from Neumagen, Germany:

Sometimes we attempt to replicate this position:

However, modern tables tend to be lower than is comfortable for this activity, and standing for long periods is tiring, so more often we use a low table and sit around it on the floor.